The Dispute Resolution Process

By Kevin Cuddihy, Contributing Writer

It’s an experience no pilot looks forward to: an e-mail from management explaining that you’ve allegedly gone astray of one of the company’s rules or regulations and must come in for a disciplinary investigation—and you’re removed from your duties until the matter is resolved. What’s your next step?

Or perhaps you get your latest paycheck and notice that one trip—the extra trip you picked up that was supposed to get you double time, per the contract—is only being paid at your regular pay rate. You know that’s not right, but how do you get it fixed?

Every pilot group has a dispute resolution process, mandated by law and detailed through collective bargaining. Pilot volunteers and ALPA staff combine to provide support when a pilot experiences an issue, but the path can sometimes be complicated.

Background

A dispute is a question about whether the contract was violated, and a grievance is the formal process for resolving a dispute as provided for in a contract.

The dispute resolution process is dictated by the Railway Labor Act (RLA) in the United States and by the Canada Labour Code (CLC) in Canada. Section 4 of the RLA states that “disputes between an employee or group of employees and a carrier or carriers by air growing out of grievances, or out of the interpretation or application of agreements concerning rates of pay, rules, or working conditions,…shall be handled in the usual manner up to and including the chief operating officer of the carrier designated to handle such disputes; but, failing to reach an adjustment in this manner, the disputes may be referred…to an appropriate adjustment board.”

Similarly, the CLC states, “Every collective agreement shall contain a provision for final settlement without stoppage of work, by arbitration or otherwise, of all differences between the parties to or employees bound by the collective agreement, concerning its interpretation, application, administration, or alleged contravention.”

Each law dictates that a process must be put in place, but neither dictates the terms of the process. This allows each pilot group to tailor the grievance process within its collective bargaining agreement in a way that best fits its needs. “The law simply says that you must have a process for resolving disputes that provides for a final and binding decision,” explains Andrew Shostack, an assistant director in ALPA’s Representation Department. “Beyond that, the parties maintain significant discretion as to how they create that process.”

Types of grievances

A pilot typically encounters two types of grievances: contract disputes (e.g., getting paid your regular rate instead of double time) and disciplinary disputes (e.g., that e-mail from management). Contract disputes involve interpretation, application, or implementation of a contractual term, while disciplinary disputes are based on some form of disciplinary action taken against a pilot.

There are three components to every grievance. First, the grievance must have merit—it must be tied to a specific section of the contract that has (allegedly) been violated or some other legitimate basis for asserting a claim. Second, a remedy must be available; there must be some way to determine damages if the grievance is granted. This usually falls under a “make whole” remedy, which seeks to put the grievant back into the position he or she would have been in had the grievance never happened. But punitive damages are extremely rare. Third, all of the contractual requirements contained within the contract’s grievance process—such as the filing timelines—must be met.

Filing a contract grievance

As noted, the grievance process is defined by each contract. The following example may not specifically apply to each ALPA pilot group, but enough comparisons can be drawn.

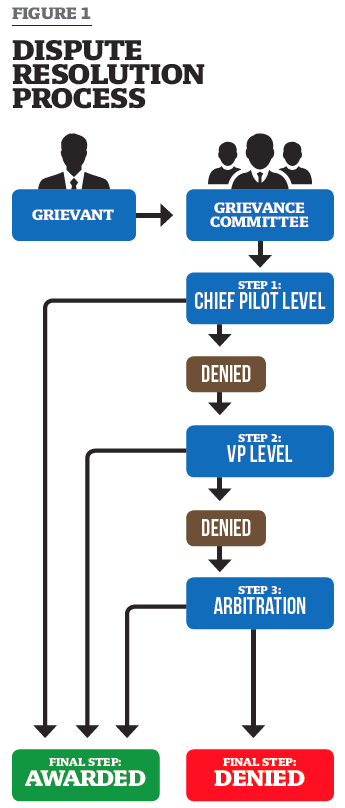

Figure 1 is a sample dispute resolution process. In many contracts, a pilot is first required to informally meet with a chief pilot about a contract dispute. If that discussion doesn’t resolve the problem, the pilot’s next step is to submit a dispute to the pilot group’s master executive council (MEC). Typically, the Grievance Committee or a subset (a Pregrievance Review Board) meets periodically to review disputes and determine how they should be addressed.

In many cases, a committee member or other MEC representative will work directly with management to resolve disputes before a formal grievance is filed. For example, a Grievance Committee volunteer or ALPA staff member interacts with the Finance Department to expeditiously resolve any paycheck mistakes, which avoids the need to file a formal grievance.

A Grievance Committee may decline to pursue a dispute on behalf of a pilot because of a few different reasons—the dispute lacks merit (e.g., there’s no basis under the contract or law to file a grievance), the costs of processing a dispute outweigh any potential benefits, the effects of a loss against the pilot group, or simply disagreeing with the asserted contractual argument. If the committee believes the company was correct in paying the pilot regular rate instead of double time according to the terms of the contract, for example, it won’t file a grievance on the pilot’s behalf.

“We’re not trying to dissuade pilots from filing a grievance,” explains Philip Thomas, a labor relations specialist in ALPA’s Representation Department. “We just want to ensure that the grievances we do file are as strong as possible.”

Most contracts require a first-step hearing in which a Grievance Committee representative, and often an ALPA staff member, presents the case to a chief pilot or other management representative. It’s not uncommon for settlements to occur at this stage (see “Resolution Options”). Failing a settlement, the chief pilot will issue a written decision, usually within a week or two.

If the decision is satisfactory in all respects—the contract violation has been recognized (company agrees you should have received double time) and a satisfactory remedy is issued (company provides back pay)—the grievance is resolved. If not, it can be appealed in the next step of the process, when available. If included, this step is very similar to the first—an informal presentation of the facts, and a written decision afterward. The Grievance Committee can include any new information learned since the first meeting.

If the dispute is resolved at this level, the process ends. But if the pilot or MEC still disagrees with the decision and wishes to further pursue the matter, there’s one final step: arbitration, referred to as the System Board of Adjustment under the RLA.

Before a grievance goes to arbitration, however, some pilot groups take advantage of a Prearbitration Review Board that they’ve established, which is similar to the Pregrievance Review Board but considers different variables. The biggest is cost; going to arbitration can in some instances cost upwards of $100,000 or more. The grievance must be worth the cost, not to mention the work that both pilots and ALPA staff will have to put into it. Other considerations include the importance of the issue to the pilots and the likelihood of success versus the potential impact of a loss.

Resolution Options

A grievance can be resolved in four ways:

1. Awarded. The company agrees with ALPA’s position and grants the grievance, including the remedy sought.

2. Denied. The company disagrees with ALPA’s position and denies the grievance. ALPA or the grievant decides not to appeal.

3. Withdrawn. ALPA or the grievant withdraws the grievance. Generally, this occurs when it’s determined that the grievance has no merit or can’t otherwise be proven.

4. Settled. The parties (company, ALPA, and grievant) mutually agree on terms that settle the dispute. This is different from the company awarding a grievance and usually involves a compromise.

Disciplinary grievances

A pilot received that unwanted e-mail and met with management (alongside ALPA volunteers and staff). After that meeting, management issues a letter within a certain number of days either closing the matter or imposing discipline. If discipline is imposed and the pilot or ALPA objects, a grievance would be filed.

A pilot is not on his or her own during this initial step. MEC representatives and ALPA staff are available to support the pilot, help investigate the matter, and argue on his or her behalf at a hearing. The work undertaken by the volunteers and staff can often be the difference between pilots being disciplined or receiving a letter clearing them in the matter.

Should the chief pilot issue a letter disciplining the pilot, the process is similar to that of a contract grievance. The committee reviews the discipline in concert with the pilot. If there’s disagreement with the verdict or even the depth of the punishment, a grievance will be filed on behalf of the pilot and the dispute (supported by ALPA staff) will go through the same steps outlined earlier to correct the discipline. (However, in some ALPA contracts, discipline cases may take priority vis-à-vis arbitration and be heard before a contract dispute.)

Arbitration

Arbitration is the final step for both types of grievances. It consists of either three or five individuals in the United States—one neutral member chosen from a list of approved arbiters either provided by the National Mediation Board or agreed to by management and ALPA, and one or two members from each side. In Canada, cases are adjudicated by just one arbitrator.

As mentioned, taking a dispute to arbitration can be expensive due to the cost of the arbitrator; flight pay loss for all pilot volunteers involved; hotel, meeting rooms, and food charges; and more. That’s why many MECs create review boards to analyze each grievance before determining whether to take it to arbitration.

Unlike the first two steps in a grievance, arbitration is a formal process. It usually includes a court reporter, federal rules of evidence, opening statements, direct and cross-examination of witnesses, objections, and questions from the neutral arbitrator. For a U.S. pilot group, a Grievance Committee and ALPA staff typically prepare a posthearing brief summarizing the argument as well (an oral closing argument takes place for Canadian pilot groups), and then the arbitrator issues a decision. The decision is final and binding and may not be appealed further except in extreme situations.

Alternatives to arbitration

There are a few alternatives to arbitration in this process, but they require management and ALPA to negotiate a letter of agreement establishing the process. One alternative is mediation in which a trained mediator attempts to help the parties reach an agreement. But unlike an arbitrator, a mediator doesn’t ultimately decide the dispute. Mediation-arbitration, or med-arb, is similar, but the mediator has the added ability to become the arbitrator and decide for both parties if they’re unable to come to a solution. And there’s also the use of expedited arbitration, or “small claims court,” in which an arbitrator is appointed to hear certain types of disputes in an expedited manner. Finally, the pilot group can take up the issue through regular negotiations, attempting to collectively bargain for specific language that would clarify the issue for both parties and (if done correctly) eliminate the problem going forward.

Conclusion

The grievance process is one mandated by law and dictated by contract. It can differ from pilot group to pilot group, but key elements remain the same. Over the years, MECs have become more vigilant in effectively managing this process and considering dispute resolution within its strategic plan. Knowing the process can help a pilot determine if he or she has a grievance, whether to proceed with it, and how to do so.

Grievance Training Seminar

The grievance process can be complicated. That’s why ALPA holds regular dispute training sessions to prepare pilot volunteers to support their colleagues. Late last year, more than 30 pilot volunteers from 10 ALPA pilot groups convened in the Association’s Herndon, Va., Conference Center for the Grievance Training Seminar.

The seminar provided the basis for the grievance procedure under the Canada Labour Code or Railway Labor Act and each pilot group’s contract, covering the wide range of jobs the volunteers undertake—from reviewing and evaluating grievances to investigating disciplinary issues to assisting in the final stage of dispute resolution, often arbitration.

The course took the pilots step by step through the grievance process, outlining their roles within each step. ALPA’s Representation Department staff conducted presentations and led discussions, and attendees viewed multiple videos that showcased how to best support their colleagues.

Presenters also provided real-life examples of situations in which volunteers might find themselves, with participants discussing how they’d handle a situation followed by feedback from the presenter. Participants were able to interact with each other as well as ALPA staff.

“Fundamentally, what you’re doing is solving problems,” explained Betty Ginsburg, director of ALPA’s Representation Department. “In many ways and at the earliest chance possible, your job is to solve problems…. You’re at the front line, and our goal with the seminar is to give you everything you need to do your job effectively.”