The State of the North American Airline Industry

By ALPA Economic & Financial Analysis Department Staff

After enduring its worst-ever down cycle in 2020 and 2021, the U.S. passenger airline industry headed into 2022 with high expectations. While the spread of the omicron variant at the beginning of the year wasn’t a positive harbinger, the impact was relatively temporary, and the industry seemed poised for a robust recovery. However, the airline industry faced additional challenges, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, record fuel prices, operational headwinds, and the delayed reopening of the large economies of China and Japan. Despite these difficulties, the U.S. passenger airline industry posted more than $5 billion in pretax profits. Looking forward, these profits are expected to more than double, reaching $13 billion in 2023.

Global Economy Shows Signs of Improvement

The same headwinds that challenged the airline passenger industry affected global economic activity in 2022. Although the economy slowed in the fourth quarter, the most recent indicators suggest that the outlook for global economic growth is improving.

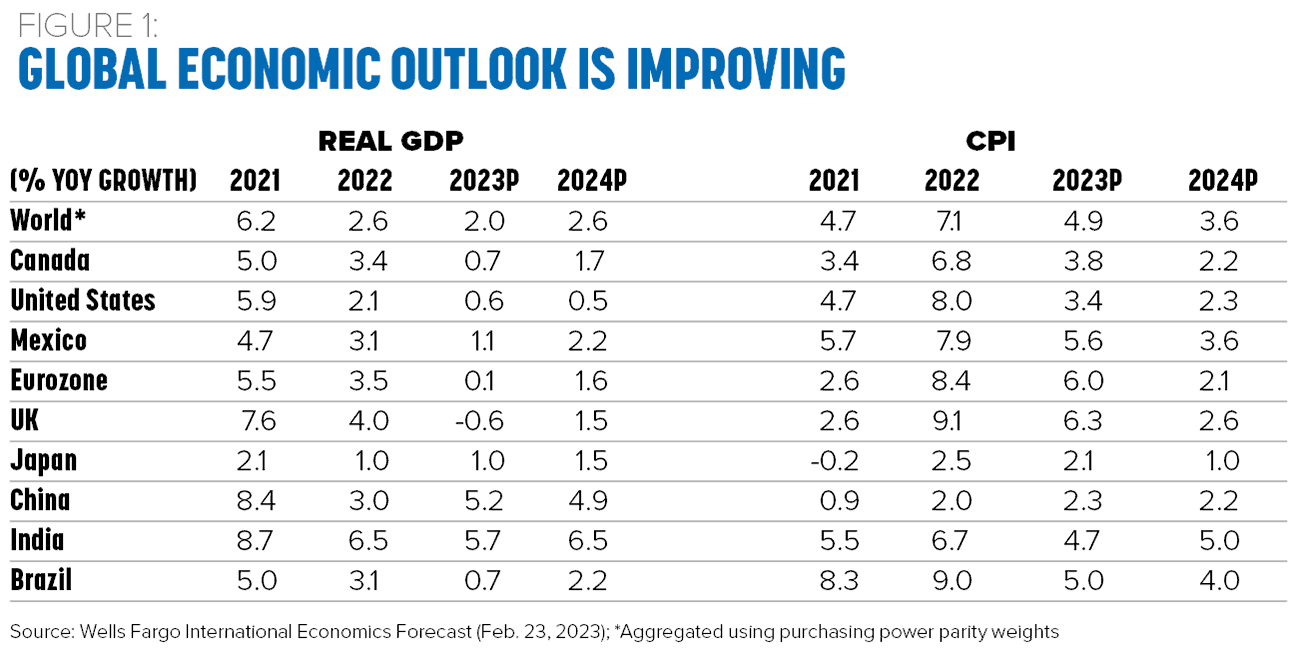

In February, Wells Fargo revised its outlook for global economic growth upward to 2 percent, compared to 1.7 percent in its December 2022 forecast. While inflationary pressures are expected to persist, Wells Fargo revised its Consumer Price Index (CPI) forecast down to 4.9 percent in 2023, compared to the December forecast of 5.1 percent (see Figure 1).

Europe’s economy was the most impacted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; however, the region’s economy is on better footing than expected. Although the war and the resultant energy crisis dampened economic activity, recent events point to positive developments. Fourth-quarter Eurozone gross domestic product (GDP) data confirmed that the region avoided the previously projected recession and raised the prospect of better-than-expected growth on the horizon.

The economic headwinds that Asia faced last year have started to fade. Global financial conditions are easing, food and oil prices are down, and China’s economy is rebounding. This should make Asia the most dynamic of the world’s major regions.

Latin America’s economies held up well last year, with the region’s economy expanding by nearly 4 percent. Employment recovered strongly, and the service sector rebounded from the damage caused by the pandemic. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), growth this year is poised to slow to 2 percent amid higher interest rates and falling commodity prices.

U.S. Economy Should Avoid a Recession

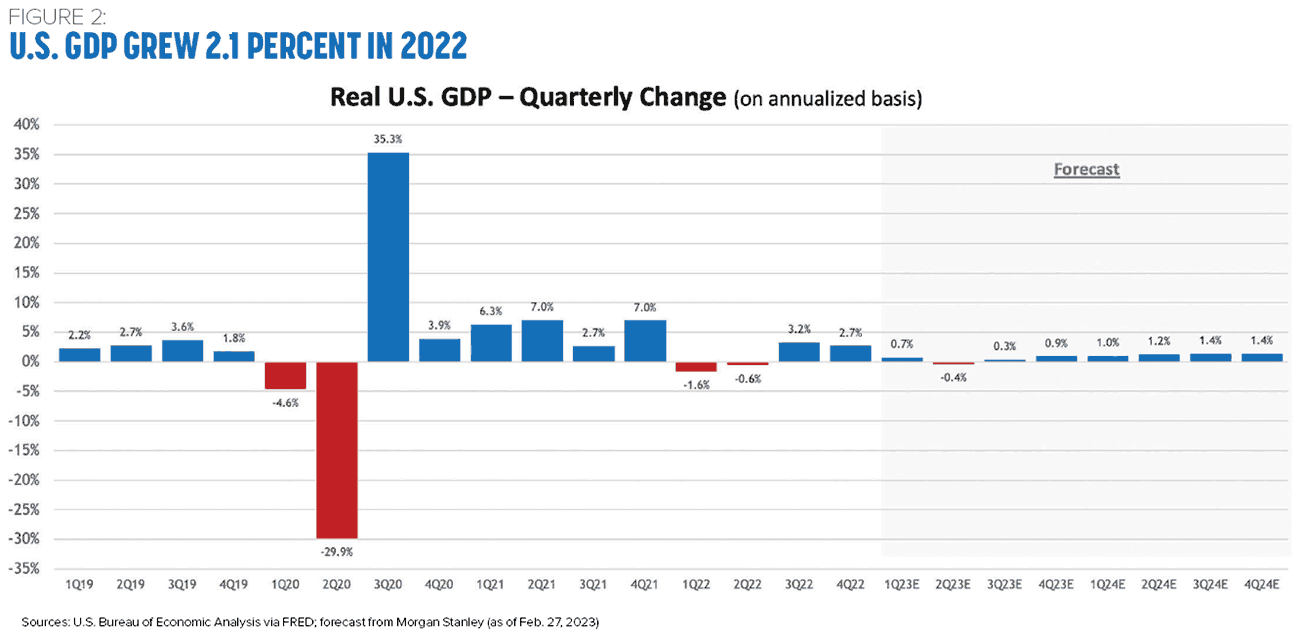

While real GDP declined in the first half of 2022, the U.S. economy rebounded in the second half of the year (see Figure 2).

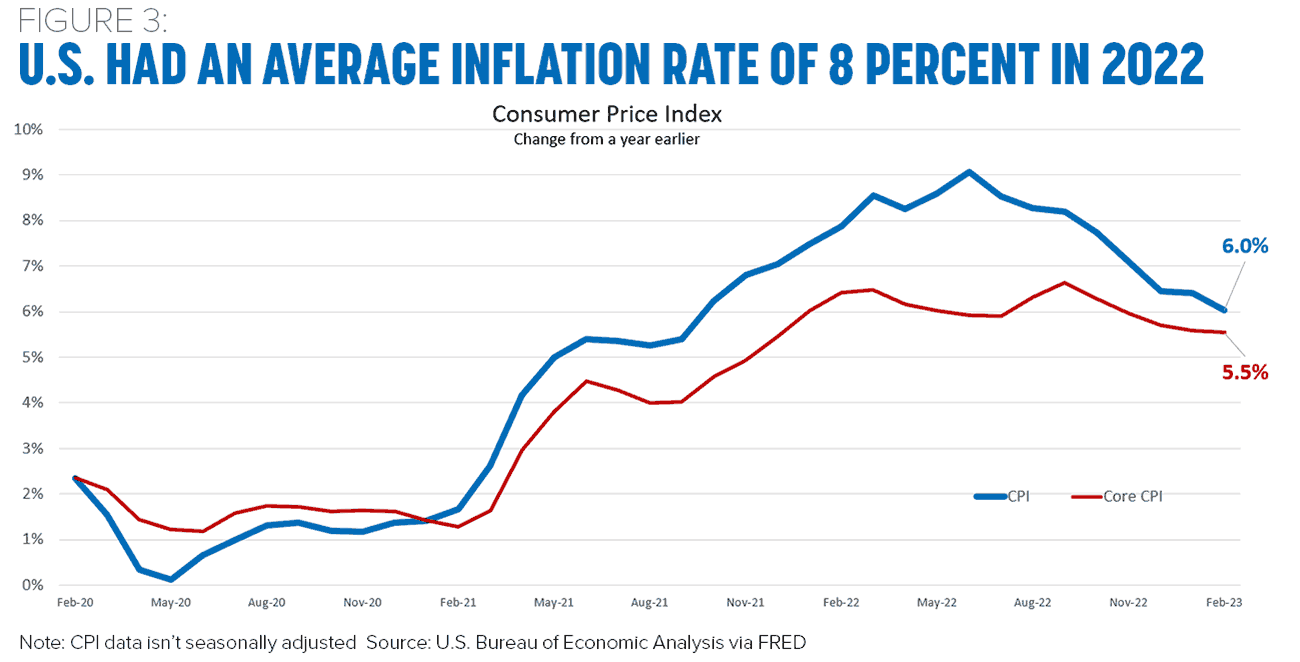

Much attention has been given to inflation, as price increases averaged 8 percent in 2022. The inflation rate peaked at 9.1 percent in June but has since decreased. February 2023 marked the eighth straight month of cooling in annual inflation, having dropped to 6 percent. Focusing on core inflation, which excludes volatile energy and food prices, the inflation rate is currently at 5.5 percent (see Figure 3).

Despite high inflation, consumers are continuing to spend. In January, overall consumer spending was 7.7 percent higher than in the last prepandemic month of February 2019, with spending on goods up 15.9 percent and spending on services up 4.2 percent.

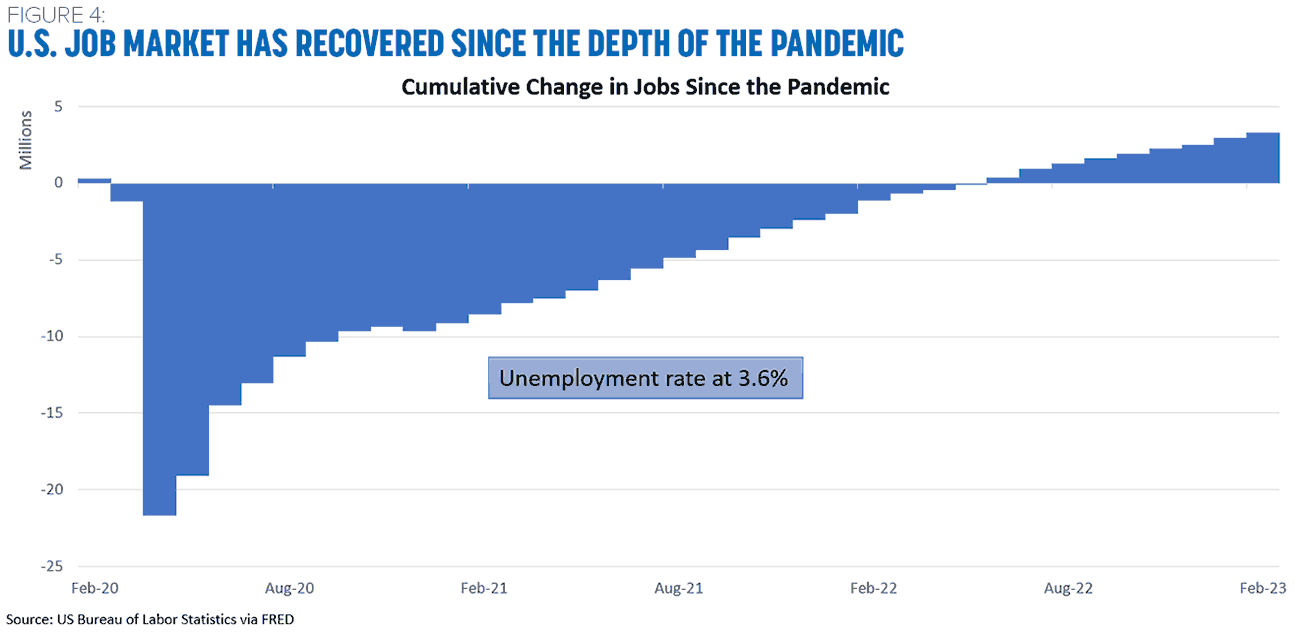

The U.S. labor market has recovered since the height of the pandemic. At its low point, the economy had lost nearly 21.7 million jobs. As of this February, the U.S. had nearly 3.3 million more jobs than it had in February 2019 (see Figure 4), and the unemployment rate was 3.6 percent. The labor market remains solid, as January had 10.8 million job openings and only 5.7 million unemployed individuals looking for work. The strong job gains helped increase the average hourly earnings for all employees by more than 5.3 percent in 2022.

The big question is whether the U.S. economy will enter a recession this year. The arrival of the next economic recession has been much speculated, but its arrival keeps being postponed—it’s always six months away. With continued strong hiring and consumer spending, coupled with U.S. households having excess savings of more than $1 trillion, the likelihood of a recession keeps diminishing. While a January Wall Street Journal poll of economists put the odds of a recession in the next 12 months at 61 percent, economists aren’t very good at predicting booms and busts in the economy. The IMF conducted a study that examined economic forecasts of 63 countries from 1992 to 2014 and one of the authors of the study concluded, “The record of failure of economists to forecast recessions is virtually unblemished.”

However, two issues are looming. If Congress doesn’t raise the debt limit before August, the federal government might not have enough cash on hand to pay its bills on time. The resulting economic pain would depend on what occurs at that point. It could range from mild, with the economy avoiding a recession, to severe, with an economic downturn similar to the global financial crisis. The other issue is the turmoil experienced recently in the banking sector. While the impact is still being evaluated, it could shave GDP growth by approximately two-tenths of a percentage point.

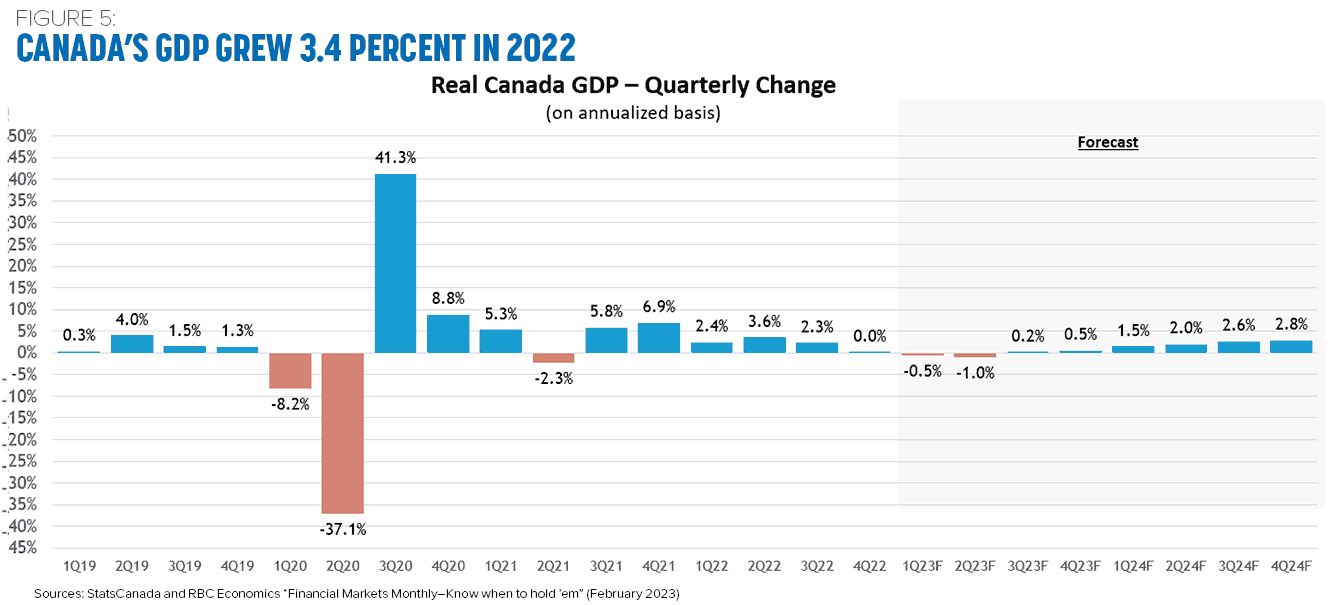

Canada’s Economy Has Fully Recovered

Canada’s GDP grew 3.4 percent in 2022, with the service sector gaining strength as health measures relaxed. After five consecutive quarters of growth, fourth-quarter GDP growth slowed and finished flat quarter over quarter, as higher interest rates impacted residential investment and businesses reduced their spending level (see Figure 5). However, Canadian consumers remained resilient, and household spending increased 2 percent quarter over quarter, with growth in both goods and services.

Like the U.S., the Canadian economy experienced a combination of tight labor conditions and high inflation in 2022. While employment took a big hit at the start of the pandemic, it’s fully recovered and is currently 4.2 percent above prepandemic levels. As of this January, unemployment was at a historic low of 5 percent. Wages increased 4.8 percent for 2022, with December capping seven consecutive months of increases of at least 5 percent.

Headline inflation for 2022 averaged 6.8 percent, the highest in more than 40 years. Consumer prices accelerated in the first half of the year fueled by higher commodity prices and the continued influence of supply-chain disruptions. Inflation peaked at 8.1 percent in June but has since moderated, as prices for energy and durable goods have decreased (see Figure 6).

For 2023, Wells Fargo is forecasting 0.7 percent growth in real GDP, followed by 1.7 percent growth in 2024.

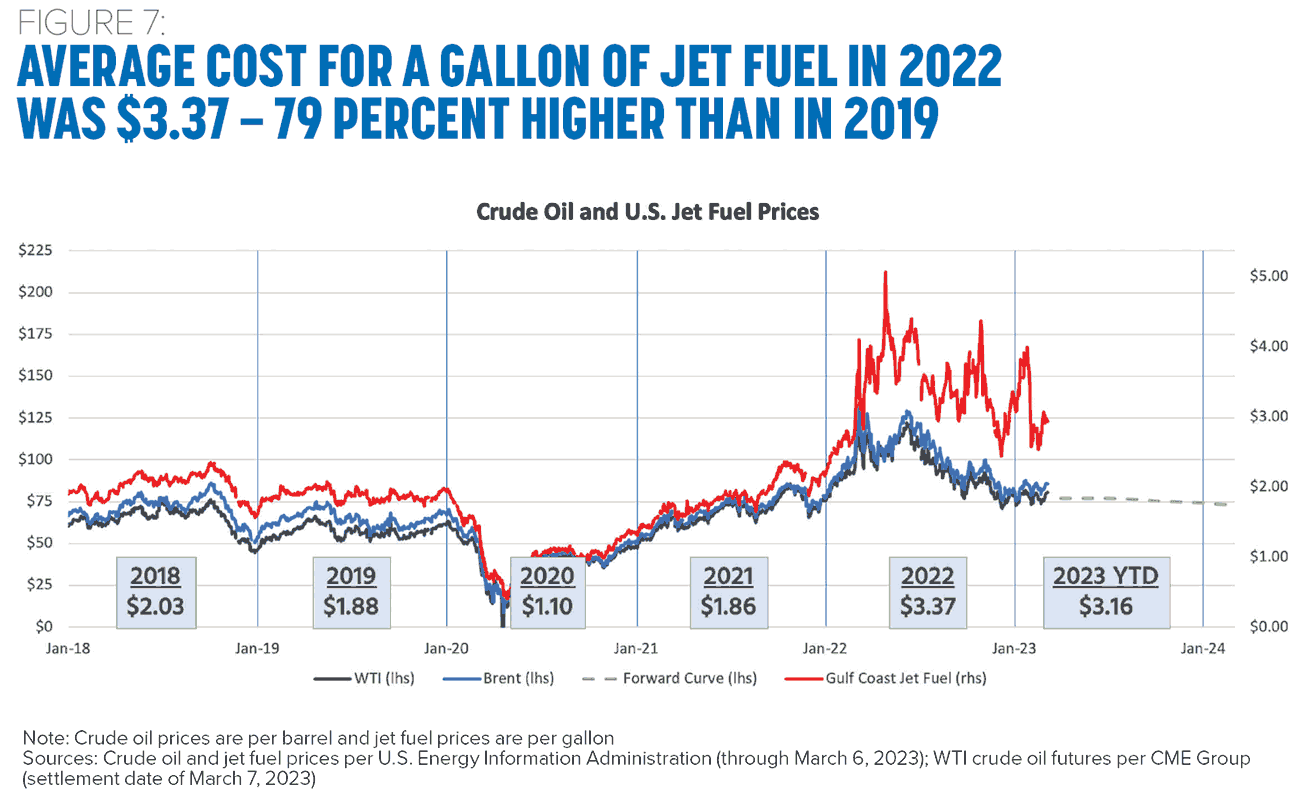

Jet Fuel Prices Increased Significantly in 2022

In 2022, jet fuel averaged $3.37 per gallon, 79 percent higher than in 2019 (see Figure 7). As a result, despite consuming 2.4 billion fewer gallons of jet fuel, large U.S. passenger airlines saw their fuel bill increase by $17.4 billion, an increase of 46 percent on 13 percent fewer gallons. To cover this cost increase, airlines needed to increase revenues by approximately 10–15 percent.

Jet fuel prices were volatile in 2022, with huge price swings occurring over very short periods of time (see Figure 7). For example, on October 20, a gallon of jet fuel cost $3.28; the price rapidly climbed to $4.37 on October 28. Just four days later, the price dropped to $3.31. Over less than two weeks, the price jumped and then dropped by more than a dollar per gallon.

In addition, the difference between the cost of jet fuel and crude oil (referred to as the crack spread) has been significantly higher since early 2022 (see Figure 7). In 2018 and 2019, the crack spread averaged about $20 per barrel; in 2022, the average was $46.78 per barrel—or $1.11 per gallon.

The industry is also experiencing large differences in the price of jet fuel depending on where the fuel is purchased. According to Argus Media, in the last week of January, the price for a gallon of jet fuel was $5.64 in New York and $3.45 in Los Angeles.

It’s expected that jet fuel prices will remain elevated in 2023 (in the $3 range) and that pricing will remain volatile.

U.S. Mainline Passenger Industry Returns to Profitability

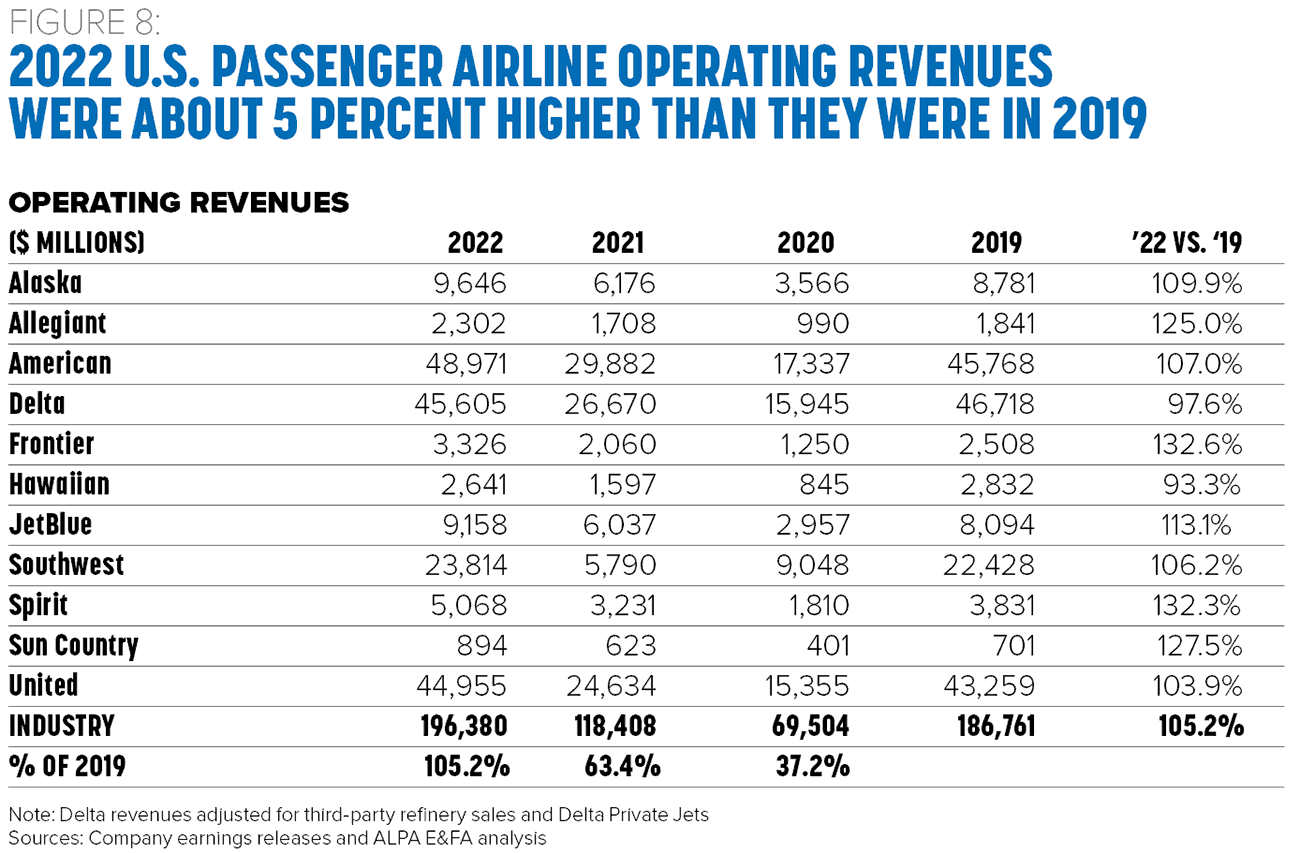

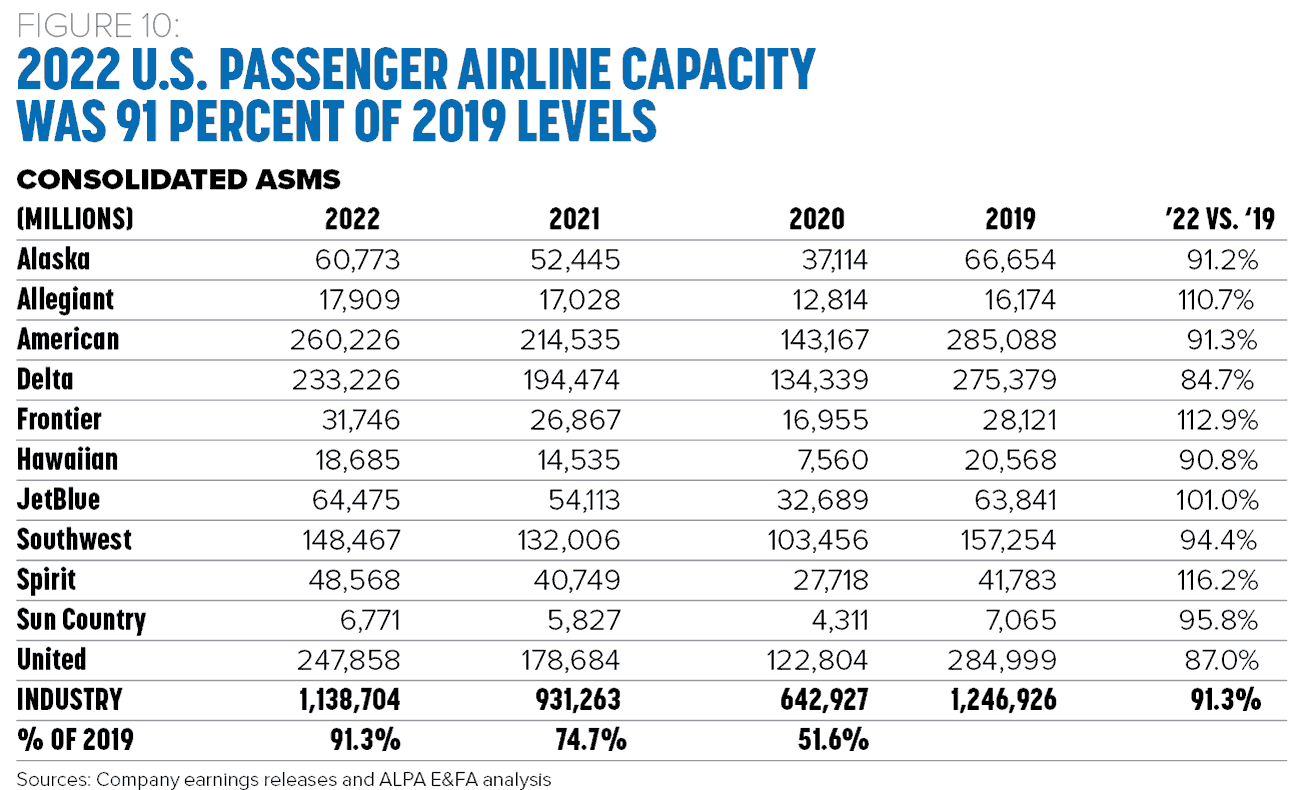

The U.S. mainline passenger airline industry experienced a robust recovery in 2022 following the turbulent pandemic years of 2020–2021. While industrywide available seat miles (ASMs) recovered in 2022 to 91.3 percent of 2019 levels, operating revenues were 5.2 percent higher than in 2019. It’s noteworthy that in 2022 the industry was able to reach higher operating revenues with lower capacity compared to 2019.

Following the losses recorded in 2020 and 2021, airline financials continued to improve in 2022. Low-cost carriers (LCCs) and ultra-low-cost carriers (ULCCs) led the industry in operating revenue increases (see Figure 8). Frontier Airlines had the highest year-over-three-year (YO3Y) increase with 32.6 percent growth in operating revenues in 2022, followed closely by Spirit Airlines with a 32.3 percent YO3Y increase. Sun Country Airlines and Allegiant Air also improved their operating revenues by more than 20 percent for the same period, at 27.6 and 25 percent, respectively. Of all the publicly traded airlines, only Delta Air Lines (on an adjusted basis) and Hawaiian Airlines posted 2022 revenues below 2019 figures.

Airline costs have been under pressure since 2020, with financial analysts predicting a reset of industry unit costs in 2023 and 2024. New labor contracts, larger labor staffing levels, and lower aircraft utilization, in addition to overall inflationary pressures, continue to be the biggest cost headwinds (excluding fuel). Adjusted cost per available seat mile, excluding fuel and special charges (CASM-ex), has increased YO3Y for all U.S. mainline carriers. Adding to unit cost pressures, the industry generated fewer ASMs in 2022 compared to 2019, thereby having a smaller base over which to spread operating costs. LCCs and ULCCs faced the largest CASM-ex rise in 2022, with Spirit leading the group at 6.4 cents in 2022 compared to 5.2 cents in 2019, an increase of 22.6 percent. Frontier followed closely with 6.5 cents CASM-ex, an increase of 19.3 percent compared to 2019. American Airlines, Delta, and United Airlines all experienced higher CASM-ex relative to 2019, but at smaller increments of 11.6, 15.3, and 12.9 percent, respectively.

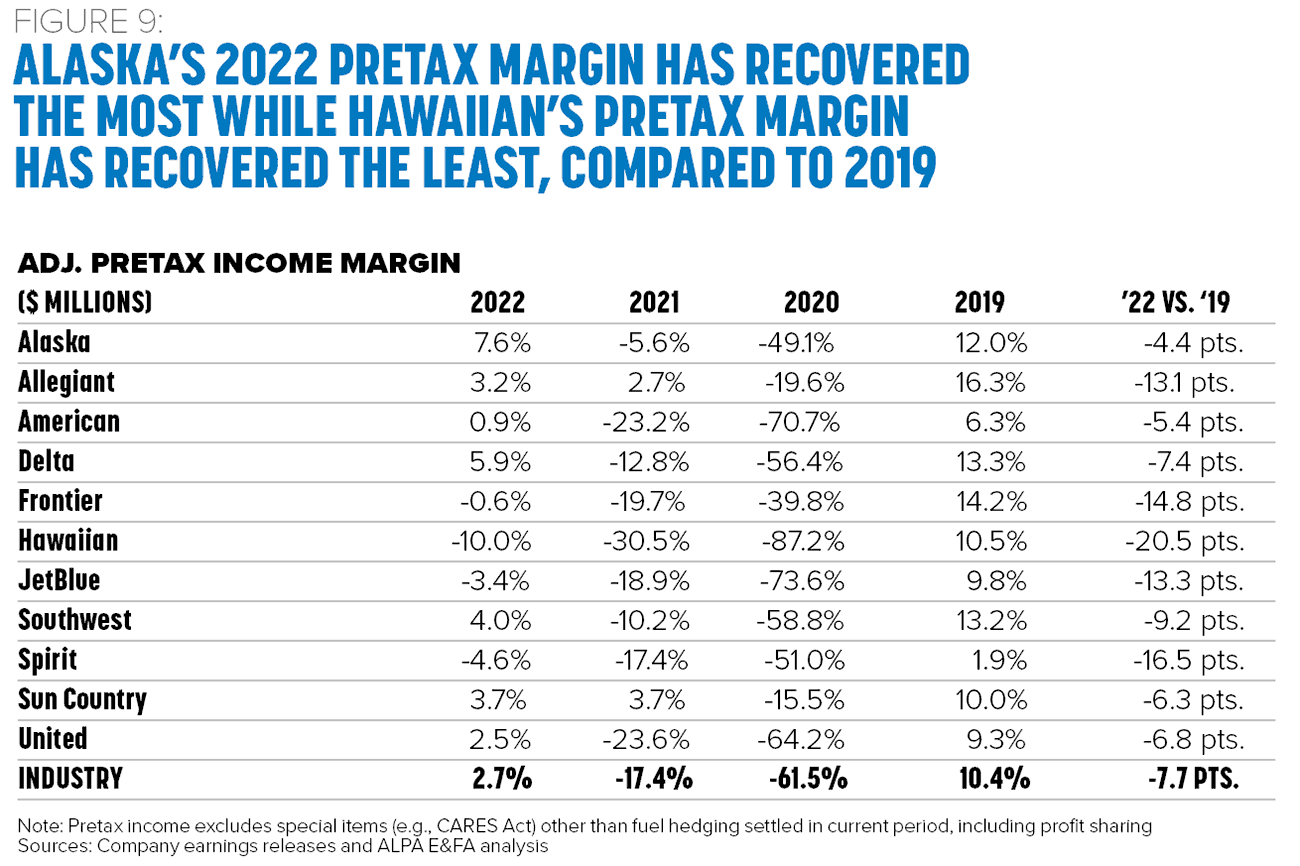

As an industry, pretax margins increased from a negative 17.4 percent in 2021 to a positive 2.7 percent in 2022 (see Figure 9). However, the industry is still down 7.7 points from 2019’s pretax margin of 10.4 percent. Alaska Airlines’ 2022 pretax margin has recovered the most compared to 2019—7.6 percent in 2022 compared to 12 percent in 2019 (-4.4 points difference). Hawaiian Airlines’ pretax margin has recovered the least—10 percent in 2022 vs. 10.5 percent in 2019 (-20.5 points difference).

Overall, industry capacity was still recovering in 2022 compared to 2019, at 91.3 percent. Delta and United had least restored their 2019 consolidated ASMs, with 84.7 percent and 87 percent, respectively (see Figure 10). LCCs and ULCCs Spirit, Frontier, Allegiant, and JetBlue Airways all increased their 2022 capacity over 2019 levels.

Though industry capacity was down in 2022 compared to 2019, 2023 is expected to surpass 2019 ASMs. Looking ahead to the first half of 2023, domestic capacity is scheduled to increase 2.6 percent compared to the same period in 2019. American and Alaska are the only carriers scheduled to produce less capacity than in the first half of 2019—down 3.5 and 0.7 percent, respectively. Meanwhile, JetBlue, Delta, United, and Southwest Airlines are all showing single-digit percentage growth in domestic capacity. ULCCs are leading the expansion of scheduled capacity, with domestic ASMs increasing 29.2 percent at Spirit, 27.8 percent at Frontier, and 16.9 percent at Allegiant.

Canadian Air Travel Recovery on Slower Pace Than U.S.

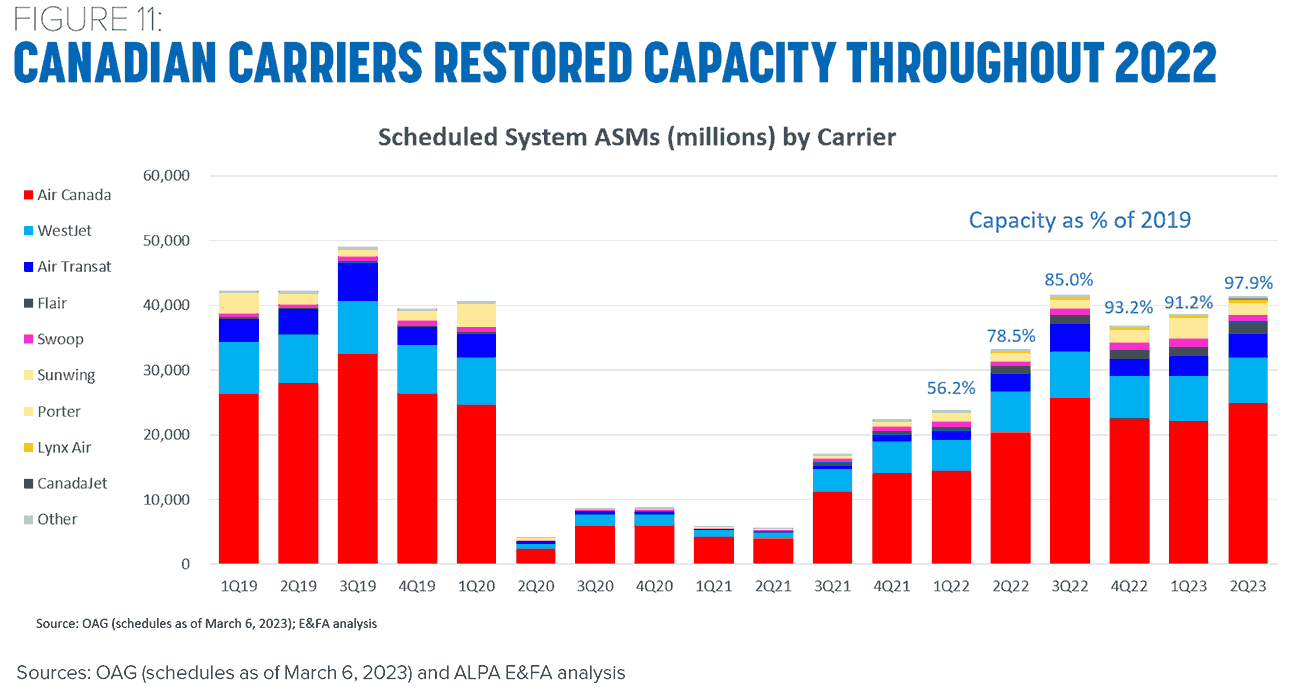

Air travel in Canada increased in 2022 as COVID measures were relaxed throughout the year. In April 2022, the Canadian government eliminated the 72-hour preflight testing requirement for travelers, and in November, COVID vaccination requirements were rescinded. Transborder travel began to rebound in June when the U.S. government stopped required COVID testing for air travelers entering the country.

As passenger traffic returned, Canadian airlines restored capacity. In the first quarter of 2022, scheduled capacity was at 56 percent of 2019 levels. Capacity increased incrementally each month thereafter, with fourth-quarter capacity reaching 93 percent of 2019 levels (see Figure 11). Overall domestic capacity was near full recovery by year-end, with incumbent network carriers (Air Canada and WestJet Airlines) at 85 percent of capacity while ULCCs had doubled their prepandemic capacity.

Looking at the first half of 2023, systemwide Canadian passenger airline capacity is currently scheduled to decrease 5.4 percent compared to the first half of 2019. Breaking that down by regions, domestic Canadian capacity is expected to be 3.6 percent above 2019 levels, while transborder capacity will be 4.9 percent lower. In the international arena, capacity to Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean will be 4.9 percent higher than in 2019. European capacity will be down slightly at -2.5 percent. As Asia continues to take longer to reopen than previously expected, capacity will remain at nearly half of 2019 levels.

Financially, 2022 saw publicly reported Canadian airlines on a path to recovery. While both Air Canada and Air Transat reported pretax losses in every quarter last year, results in the second half of the year were better. While the inflationary impact on costs remains challenging, the improved pricing environment provides a buffer. Current booking trends indicate strong consumer demand for travel. Partly because of the pandemic, Canadian airlines continue to carry high levels of debt and are seeking paths to deleverage as financial results normalize and carriers consistently generate strong cash flows.

Many industry developments occurred in 2022, most notably WestJet announcing its purchase of Sunwing Airlines and retrenchment to Calgary, Alb. WestJet pulled back operations in eastern Canada, including international flying out of Toronto, Ont., and significantly shifted resources to focus on its network in western Canada while leveraging relationships with Delta, KLM Airlines, Korean Air, Japan Airlines, and eastern Canada’s Air Transat. Air Canada has continued to develop its network through a transborder joint business agreement with its Star Alliance partner United along with a new partnership with Emirates that will expand its reach into Africa and the Middle East.

Canada’s landscape will see increased competition. While incumbent carriers continue their network expansion through a combination of capacity deployment and code-share relationships, the Canadian ULCC segment is on the precipice of remarkable growth. Flair Airlines, Porter Airlines, Lynx Air, and WestJet’s Swoop are looking to boost capacity by 30 percent for the first half of 2023 compared to last year. In addition, these carriers have aggressive fleet growth planned over the next several years.

However, several Canadian aviation industry analysts warn these growth plans may not materialize due to infrastructure constraints (e.g., airports) and the inability of these airlines to access both financial and human capital. Analysts see the potential of a repeat of the late 1990s to early 2000s when competition from a slew of new entrants led to a period of depressed airfares in the industry.

While the Canadian airline industry’s recovery has lagged the U.S. industry’s recovery, National Bank of Canada recently noted that, based on historical passenger growth and GDP trends, the Canadian passenger industry has further room for improvement beyond 2019 levels. In addition, growth rates could surpass the historical range for several years as the industry catches up to the prepandemic trendline.

FFD Industry Continues to Evolve

The fee-for-departure (FFD) industry looks a lot different in the postpandemic era, with numerous changes ranging from the number of airlines, agreements with mainline carriers, and contract enhancements. At the beginning of the pandemic, Trans States Airlines and Compass Airlines ceased operations. Months later, ExpressJet shut down but reemerged for a short period as low-cost carrier Aha! only to file for bankruptcy in August 2022.

In 2023, Air Wisconsin and Mesa will change mainline partners. After previously flying for United, Air Wisconsin will shift to American and transition its fleet to American Eagle. Mesa has agreed to fly exclusively for United, moving its CRJ900 fleet from American Eagle to United Express.

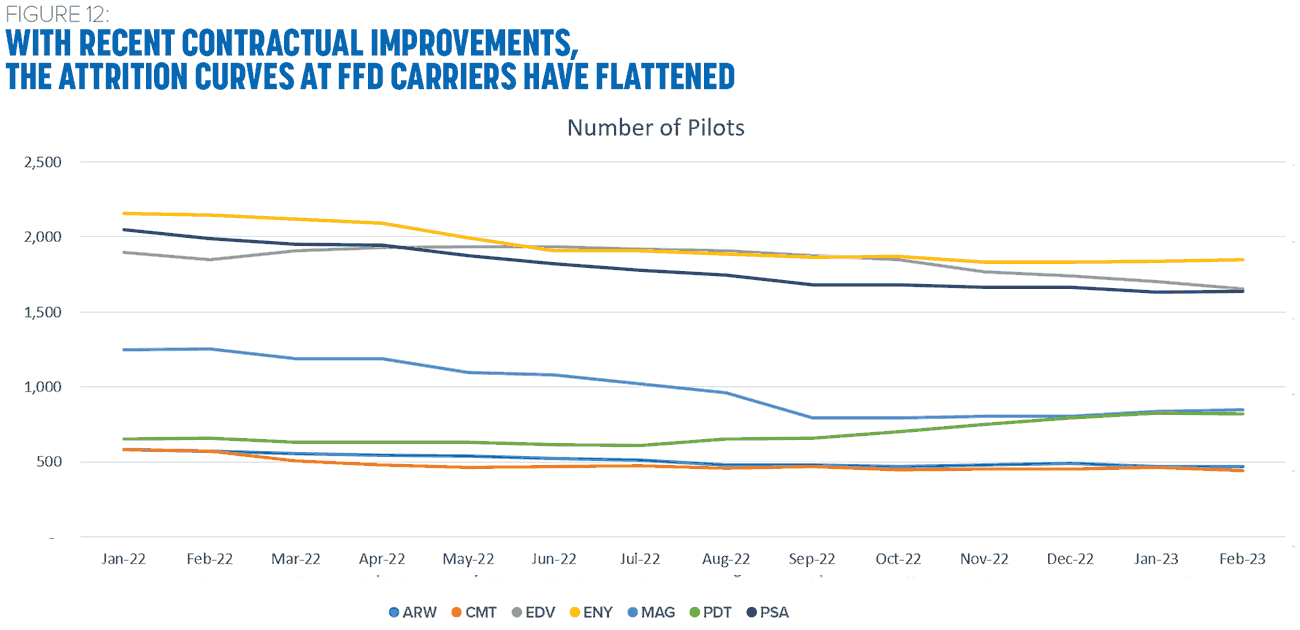

In February 2022, CommuteAir kicked off FFD contract improvements by ratifying a four-year collective bargaining agreement that included more than 25 percent pay increases for captains and 32 percent pay increases for first officers. This deal reset the market for FFD carriers. In June 2022, Mesa’s Master Executive Council approved a tentative agreement; however, five days before the vote opened, Envoy Air, Piedmont Airlines, and PSA Airlines—the three wholly owned American subsidiaries—reached agreements containing unprecedented pay rates and other contract enhancements. These three agreements included bonuses and 50 percent pay rate premiums, scheduling and work-rule improvements, flow agreements to American, and other quality-of-life improvements. As a result, Mesa pilots overwhelmingly rejected the tentative agreement and returned to the negotiating table seeking better pay rates. Less than two months later, a letter of agreement was reached with first-year captains and new-hire first officers receiving pay rate increases of nearly 118 percent and 172 percent, respectively.

With these large rate increases, Endeavor Air pilots, who started 2022 with the highest pay rates in the FFD sector, suddenly found themselves near the bottom of the industry. In October, Endeavor pilots reached an agreement that not only brought their pay rates back to the top of the FFD industry, but also included many quality-of-life improvements. Air Wisconsin also struck a letter of agreement in late 2022 to increase pay rates 25 percent for all pilots; however, even with the increase, their pay rates remain near the bottom of the FFD sector.

All of these compensation and quality-of-life improvements were necessary to ease the increased attrition at FFD airlines. As these agreements were reached throughout 2022, the full effect of these improvements has yet to be realized. Piedmont was the only FFD carrier to have more pilots at the end of 2022 than at the start of the year. The attrition curves at each carrier flattened to some extent compared to the declines experienced before these agreements were reached (see Figure 12). As pilots leave for larger carriers, some due to mainline flow agreements reached in 2022, FFD carriers will need to continue to find ways to attract and retain pilots to reduce the attrition experienced in recent years.

With domestic COVID restrictions in the rearview mirror, regional air travel has returned, which should lead to hiring outpacing attrition. The agreements reached in 2022 have had positive effects across the FFD industry, as this sector will continue to be the “foot in the door” for aspiring airline pilots. As the number of pilots with air transport pilot certificates increases, these newly certified pilots now have an improved career path thanks to FFD contract improvements.

After Robust Growth, Cargo Industry Expected to Return to More Normalized Levels

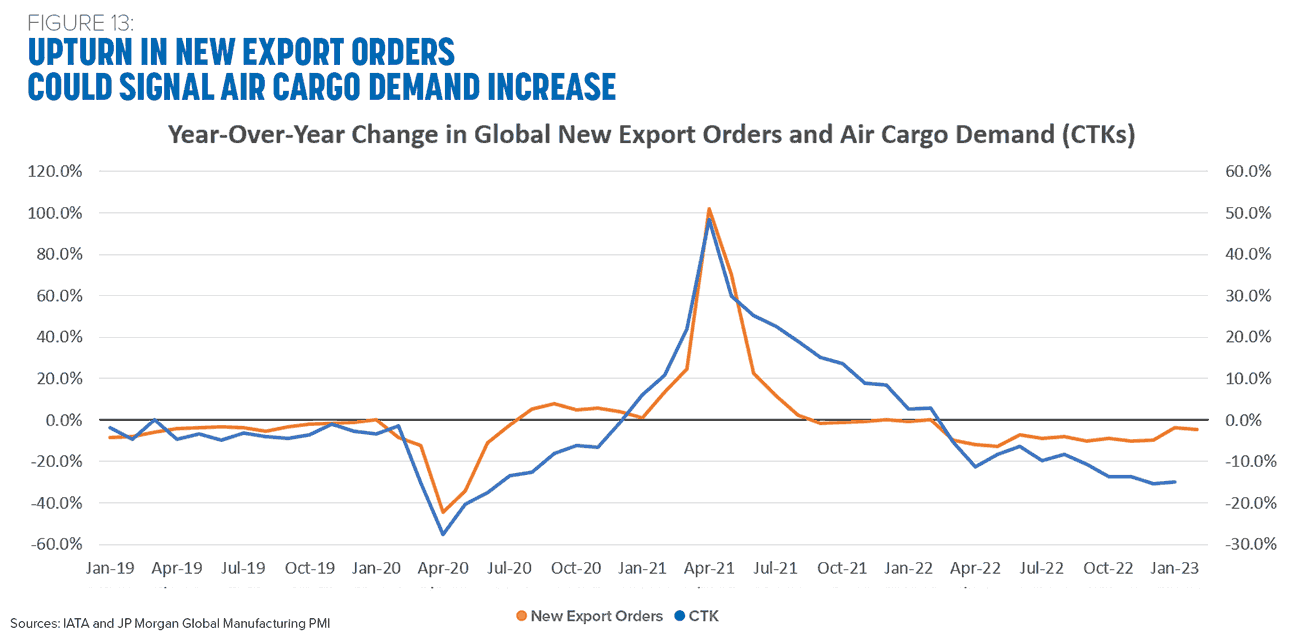

After experiencing two robust years of air cargo demand during the pandemic, the air cargo industry saw slowing demand in 2022 (see Figure 13). However, after a sluggish start, the industry is expected to return to more normalized levels in 2023.

Air cargo demand is typically driven by seasonal events. The biggest peak season runs from late October through December, as retailers prepare for the holiday shopping season. Another peak in air cargo demand occurs after the Chinese New Year, when Chinese manufacturing ramps up again after the post-holiday slowdown. Additionally, air cargo experiences smaller peaks throughout the year, such as flower shipments prior to Valentine’s Day and back-to-school supplies at the end of summer.

Major lockdowns in China due to omicron, the war in Ukraine, increased fuel prices, supply-chain disruptions, and inflation all combined to push cargo demand lower from March 2022 onward. In addition, demand for air cargo fell as consumers began shifting their spending more toward services instead of goods, retailers adjusted their inventory levels in the face of slowing global economy, and freight forwarders shifted some of their transportation needs back to ocean shipping as ocean schedule reliability improved.

Global cargo demand, measured by cargo ton kilometers (CTKs), declined 8 percent in 2022 compared to 2021 and 1.6 percent compared to 2019 levels. Carriers in North America, which make up approximately 28 percent of the market, saw demand slip just 5.1 percent in 2022. All other regions, except Latin America, which is just under 3 percent of the market, saw a decrease of nearly 10 percent or more.

This January, the global air cargo industry posted a 14.9 percent decline in CTKs, although the traffic for North American carriers was down 8.7 percent compared to last year. While this figure indicates the industry is off to a slow start, recent anecdotal data suggests a stabilization in air cargo demand may be on the way.

The new export orders component of the Global Manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) is typically viewed as a leading indicator for air freight. The PMI for the last half of 2022 for most major economies indicated zero or negative growth. There are signs of improvement, however, as the February PMI pointed to expansion as supply-chain constraints ease and China’s economy reopens (see Figure 13).

According to some sources, the pandemic accelerated the shift from brick-and-mortar stores to online shopping by approximately five years. E-commerce reached record levels in 2021, with nearly a quarter of the world’s population shopping online, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA). Recent data suggests that the initial e-commerce estimates of 11 percent annual growth were perhaps too optimistic, but significant growth is still expected. In the U.S., e-commerce sales grew 52.7 percent in the first quarter of the pandemic and were 16.4 percent of total retail sales. The latest data showed e-commerce sales growth slowed to 6.5 percent on a year-over-year basis, comprising 14.7 percent of total retail sales. UBS Evidence Lab now estimates that e-commerce sales will rise at a 6 percent annual growth rate and that e-commerce sales will approach a 20 percent share of retail sales in the next four years.

While retailers adjusted their inventory levels in the face of slowing demand, there are signs that they may need to restock their supply in the second half of 2023. Target and Macy’s recently reported their inventory levels had declined 3 percent from a year ago, while Walmart’s inventory levels were even with a year ago. Meanwhile other department store chains saw inventory levels fall between 11 and 15 percent from last year.

Inventory restocking, continuing strong e-commerce demand, and a ramp-up in global manufacturing all point to a stabilizing air cargo demand environment. While some capacity adjustments are still being normalized from the swings of the pandemic, yields and revenues should hold up.

For 2022, global air cargo capacity, measured in available cargo ton kilometers (ACTKs), was up 3 percent year over year but was still 8.2 percent below 2019 levels. Air cargo carried in the belly of passenger aircraft historically made up between 50 to 60 percent of the capacity in the industry. When the pandemic shut down international travel, that belly capacity was wiped out and dedicated freighters were nearly the entire market for capacity, supplemented by capacity being flown by “preighters”—passenger aircraft with freight in the main cabins. As the international passenger industry began to recover in 2022, belly capacity became available once again. This January, international ACTKs for belly cargo grew 50 percent year over year and reached 71 percent of prepandemic levels. In contrast, international cargo capacity provided by dedicated freighters experienced a year-over-year decline of 11 percent.

Overall, as demand has been falling since spring 2022, supply has been generally increasing. The most recent data shows that global air cargo capacity was up 3.9 percent year over year in January. North American carriers recorded a 4.2 percent increase in capacity for 2022 over 2021 and a 2.5 percent annual growth in January.

While these figures are illustrative of the overall industry, the addition and contraction of air cargo supply has varied wildly from airline to airline, with significant changes just recently announced. For example, ATSG—the parent company of Air Transport International and ABX Air—recently noted that eight of the 12 B-767 freighters Amazon leases won’t be renewed. Yet, Amazon has contracted with Hawaiian to fly 10 A330 freighters with deliveries set to begin in late 2023. And Mesa has acquired another converted freighter to meet the demands of DHL, expanding its freighters to four, with an eye toward adding more as cargo demand recovers.

Another reduction in capacity was recently announced by Cargojet. The company signed a letter of intent to sell two B-777-300s in February, citing the recent slowdown in the global economy as the reason. These aircraft were meant to expand the carrier’s international reach and were part of six aircraft expected to be flown for DHL as part of a broader five-year contract.

In further changes to cargo capacity, FedEx Express announced it parked an additional nine aircraft, reducing flight hours by 8 percent and downgauging on certain routes during its most recent quarter ending this February. The company also projected it would park an additional six aircraft by the end of May. As of last November, FedEx still showed an expected delivery of 29 B-767Fs and six B-777Fs through FY 2025 as part of its fleet modernization program.

WestJet Cargo was scheduled to begin service in late March with four dedicated B-737-800 NG freighters out of Toronto. UPS placed an order for eight more B-767 freighters last August, in addition to the 19 ordered in December 2021. The company is expected to take delivery of the freighters in 2025 and will take delivery of a B-767BCF this year.

With the decline in demand and increase in supply, the air cargo industry load factor in 2022 was 50.1 percent, falling six percentage points compared to 2021. However, the cargo load factor was still three percentage points higher than in 2019.

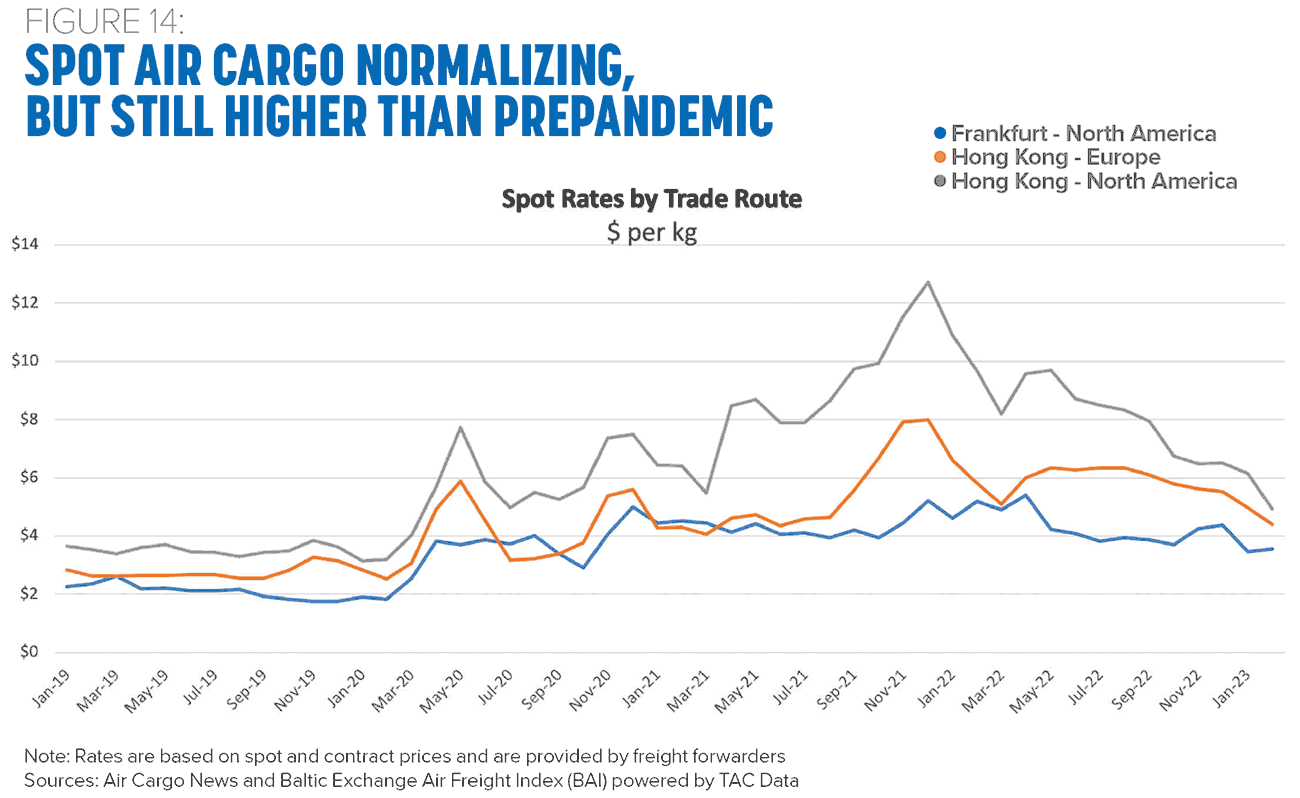

Air freight rates in the spot market have decreased from pandemic highs, when the lack of belly space and ocean reliability helped to push rates to record highs. Industry data source Xenata recently posted that while global air freight rates had fallen 35 percent from a year ago, they were still 52 percent higher than in 2019. Looking at rates for specific routes, Frankfurt-North America has experienced the lowest decline, while Hong Kong-North America has seen the largest decline—albeit on the back of the highest rate increases (see Figure 14). There are indications that spot rates may be headed higher again. The most recent weekly data from TAC Index, a publisher of weekly average general cargo prices, noted that the overall Baltic Air Freight Index covering prices by freight forwarders rose 3.5 percent in the first week of March.

IATA forecasts that global cargo revenue will be $149.4 billion in 2023. This figure is down from the record set in 2021 when cargo revenue was $204.2 billion, but well above the 2019 mark of $100.8 billion. Despite cargo demand moderating, revenue levels for the industry are likely to continue to surpass prepandemic levels, even with increased pressure on yields as belly capacity returns.

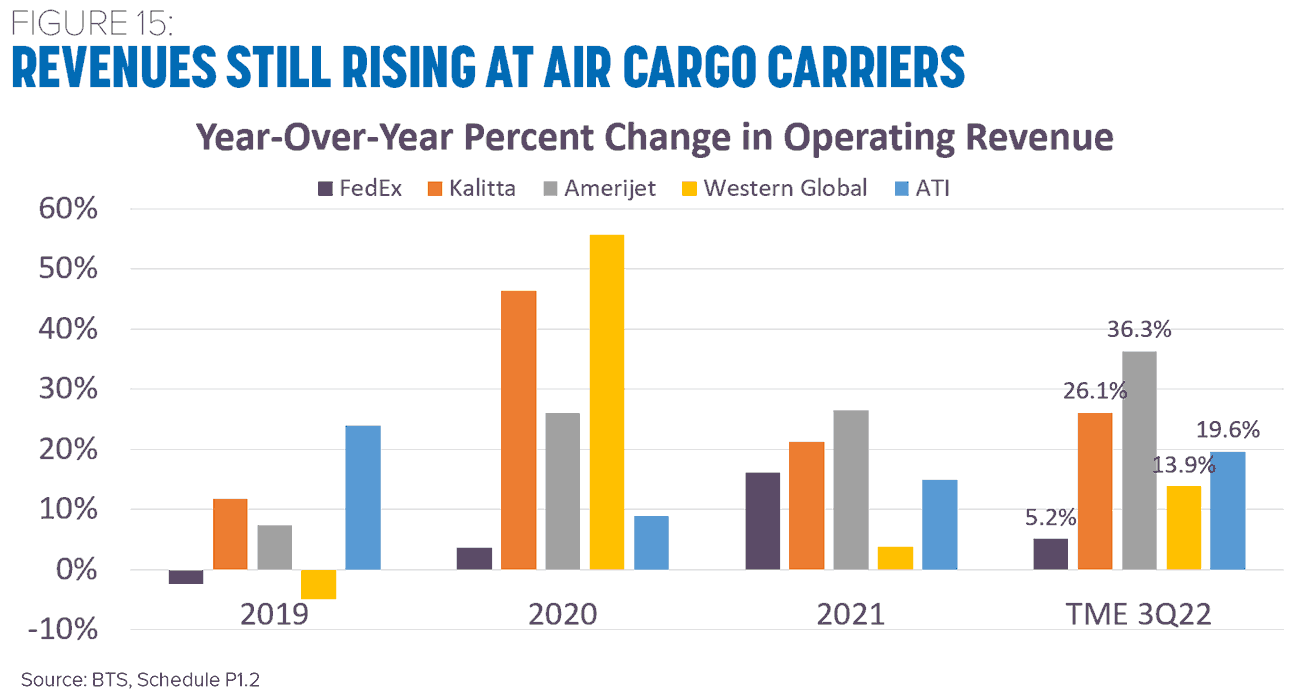

Revenue figures for several major cargo carriers show that despite a slowing trend for cargo demand, high yields have allowed revenue to continue to grow. According to the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, for the 12 months ending September 2022, Air Transport International, Kalitta, Amerijet, and Western Global had an average increase in revenue of 25 percent from the same period a year earlier, while FedEx revenues were up more than 5 percent (see Figure 15). And in Canada, Cargojet posted a 30 percent revenue increase in 2022 vs. 2021.

Globally, the air cargo industry is expected to face various headwinds in the near future, and some carriers have scaled back dedicated freighter capacity in the face of these near-term challenges. However, there’s still demand in the market as many shippers have come to expect that capacity will be available and ready when needed—and history shows they’re willing to pay for it. Thus far, air cargo yield and revenue remain above 2019 levels, and further growth remains a real possibility.

Outlook for 2023 Is Positive

The U.S. mainline passenger industry suffered through the worst downturn in its history in 2020–2021. But 2022 marked the beginning of the recovery, and most carriers were able to return to profitability. This upward trend is expected to continue into 2023, as strong demand for travel should translate into improving profits.

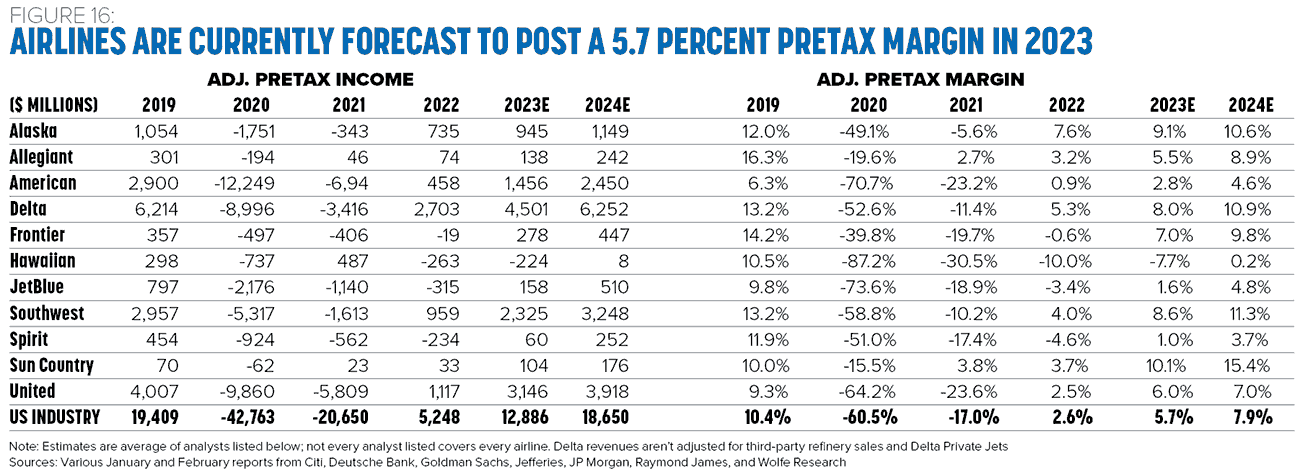

While airlines will continue to face inflationary cost pressures, the investment community is forecasting that 2023 profits should more than double 2022 profits. Furthermore, it’s predicted that profits in 2024 should approach 2019 levels (see Figure 16).

For freight carriers, while demand and pricing softened in 2022 from the highs of 2021, revenues should continue to be well above prepandemic levels.

ALPA’s Economic & Financial Analysis Department will continue to track and examine the various economic and financial indicators that impact the airline industry, as these factors play a crucial role in the career of the Association’s members and the overall airline piloting profession.