What Happens After a Bird Strike?

An Atlantic Southeast Airlines CRJ200ER after a bird strike in 2011.

ALPA has been a long-standing advocate for reducing the number and severity of bird strikes. In concert with other industry stakeholders, ALPA safety representatives have worked tirelessly to refine training procedures and promote advancements in detection and warning technologies and partner with government and industry to improve aircraft and engine designs as well as regulations.

The Association’s safety representatives also work with individual airports through ALPA’s Airport Safety Liaison program to give managers and officials the line pilot’s perspective on ways to improve wildlife mitigation programs. ALPA reps also work with Bird Strike Committee USA to share information on reducing wildlife hazards and to promote awareness.

However, while numerous prevention practices are at work, bird strikes still occur. And when one does happen, a report is normally filled out, and what remains of the struck bird is gathered by ground crews and mailed away for expert analysis. So what happens next?

Arrival

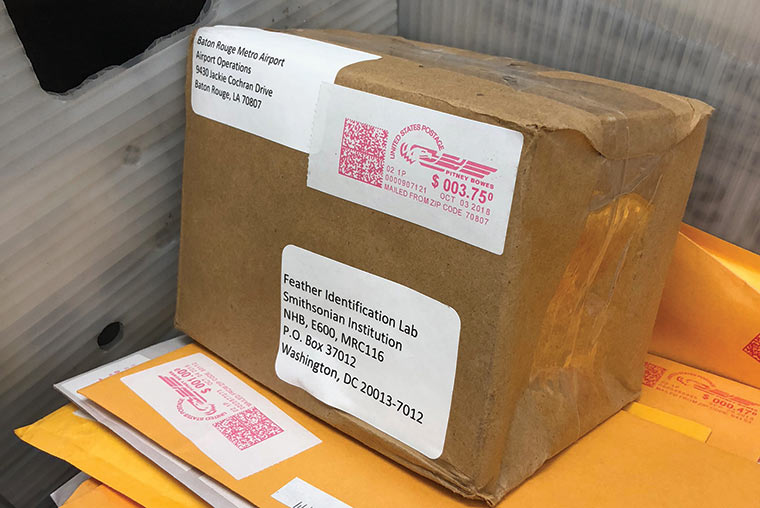

Any collected feathers, remains, and “snarge”—the residue smeared on an airplane after a bird/airplane collision—are sent to the Smithsonian Institution’s Feather Identification Lab for processing. Located on the sixth floor of the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., the lab’s collection of 600,000 specimens spans 150 years and serves not only as a time capsule, but as a unique resource documenting birds through various seasons, years, and locations.

“Our collection was started for tracking the evolution of bird species,” said Dr. Carla Dove, a forensic ornithologist and the lab’s program manager. “The archive houses more than 85 percent of the 10,000 documented bird species. Of those, the data shows that only 575 species have been involved in bird strikes.”

When collected remains arrive at the lab, they’re logged into the database along with pertinent facts, and a QR tracking code is assigned to the file. Priority cases, those that involve serious damage or fatalities, are fast-tracked into the system. The remains—whole feathers, bone, fat tissue, or viscera—are studied to determine what materials are present and then a small sample is taken for DNA analysis.

Bird remains arrive at the lab in packages of all shapes and sizes from around the world.

Even trace amounts of bird feathers can yield clues into a bird’s origins.

Fledgling Science

The science of forensic ornithology was pioneered by Roxie Laybourne, who in 1960 identified the type of birds (starlings) involved in an aircraft accident from charred fragments that clogged the engines. She later developed microscopic procedures for identifying birds from fragmentary remnants.

“While the tips of the feather may appear to be distinctive, it’s the downy material, and the structure of the barbs and barbules near the quill, that provide the information we truly can use,” said Dove. “We examine the feathers under a microscope and compare the morphology of the collected specimen with our reference samples to determine species.

“Of course, we always want as much of the matter as possible,” Dove continued, “because the more data points we have for comparison, the more confidence we’ll have in making our identification.” The data is then correlated with research from field guides on the documented range of particular species to see if the determination makes sense.

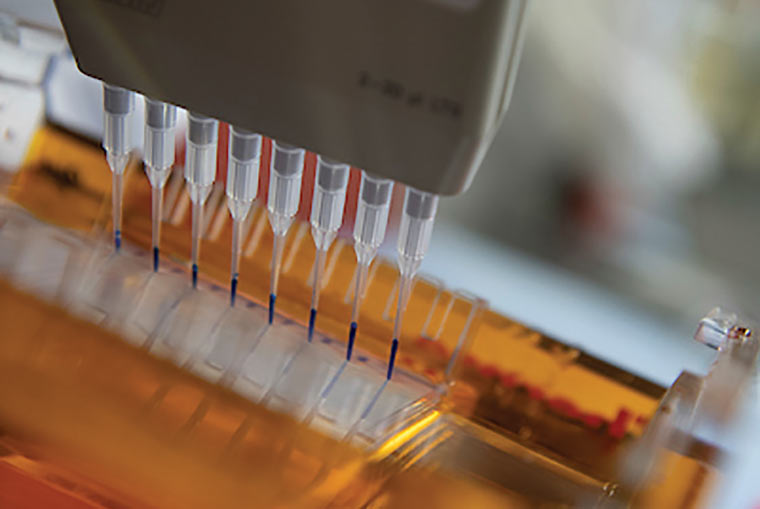

Scientists must be careful when isolating samples for DNA analysis.

Advances in DNA sequencing technology are changing the science of identification.

Technological Advances

The lab also uses DNA processing equipment to analyze samples. After a four-hour automated process to isolate a DNA profile proves successful, that DNA sequence is then compared with an online reference database of mitochondrial sequences known as the Barcode of Life Data Systems—a repository of more than 5.9 million DNA barcode sequences from more than 542,000 species worldwide. According to Dove, “We typically get a good profile from a sample, as we’ll make three attempts on each sample to isolate a DNA sequence. The database can generally match to the species level. We use a different molecular technique to determine the sex of birds if the weight difference is necessary for engineering questions.”

The addition of DNA sequencing has boosted the lab’s identification rate, and advances in genetics and biology continue to increase the amount of information obtained from DNA sequencing. “In the future, we hope to be able to make individual identifications—separating different birds of the same species, as we’d like to be able to tell definitively if a single bird was involved in the mishap or whether multiple birds were responsible.”

Turnaround Time

The lab typically takes a week to make a determination, and then the findings are immediately given to the airport to help with wildlife management programs and added to the FAA’s online Wildlife Strike Database, which contains records of all reported wildlife strikes since 1990. Identifying bird species involved in strikes is an important part of the overall assessment and management of wildlife mitigation at airports.

“We don’t tell the airport or anyone what to do with the information since that isn’t our expertise,” Dove remarked. “However, if airport managers know exactly what bird species is causing issues, they can redirect their resources and change their methods and tracking trends, as well as focus on preventative measures like wildlife habitat management and other avoidance programs. And the data can have an even further impact beyond just an airport. It’s been used to develop safety improvements for aircraft engines and windshields.”

By the Numbers

According to Dove, horned larks are the species identified in most bird strikes, followed closely by mourning doves. “That said, Canadian geese still do the most damage due to their sheer size and weight.” Processing nearly 10,000 cases per year, the lab’s peak season is September and October, the time when many birds migrate to warmer climates. Collected remains from nondamaging strikes are held for two years; but if damage is reported, everything is kept indefinitely as part of the historical record. The lab and its team of five researchers are jointly funded by the FAA, the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Navy, and the Smithsonian Institution and operates on an annual budget of approximately $800,000, which is an amazing value since the information provided actively prevents damage to aircraft and loss of life.

While reporting bird strikes is still voluntary under FAA regulations, Dove praises ALPA’s participation and the work of pilots, noting, “Since the 2009 ‘Miracle on the Hudson’ incident, pilots have become much better at documenting bird strikes. The reports really do go somewhere, the data is collected and processed, and the information shared so that improvements are made and lives saved.”

Dr. Carla Dove, program manager of the Smithsonian Institution’s Feather Identification Lab.

Feathers have characteristics unique to each bird species.

Help Build the Database

Photos: James Kegley, Feather Identification Lab, Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History; Getty Images; Associated Press